The Evolution and Revolution of Pig Husbandry

Pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) are among the earliest animals domesticated by humans. Their domestication and global spread underscore their significance as a reliable, versatile, and productive source of food. Pigs have thrived in diverse environments and played integral roles in cultural practices worldwide, making them one of humanity’s most important domesticated animals. This story began 9,000 years ago and continues to evolve, opening a new chapter in history with the arrival of Pig brother – and AGRI-FOOD.AI.

Chapter 1 – From Boar to Pig

The wild ancestor of domestic pigs is the Eurasian wild boar (Sus scrofa), native to much of Eurasia and North Africa. Pigs were domesticated independently in multiple locations, with the two primary centers believed to be the Near East (modern-day Turkey and neighboring regions) and East Asia (especially in China). In the Near East, archaeological evidence suggests that pigs were domesticated around 9,000 years ago, alongside goats, sheep, and cattle. This process likely involved taming wild boars attracted to human settlements where they scavenged for food. Over time, these animals became more accustomed to human presence, and selective breeding led to desirable domestication traits such as reduced aggression and smaller size.

In East Asia, particularly the Yangtze River Valley, pigs were also domesticated independently, possibly even earlier than in the Near East. Genetic studies indicate some interbreeding between domesticated pigs from these regions, though the distinct genetic lineages suggest separate domestication processes.

Chapter 2 – The Spread

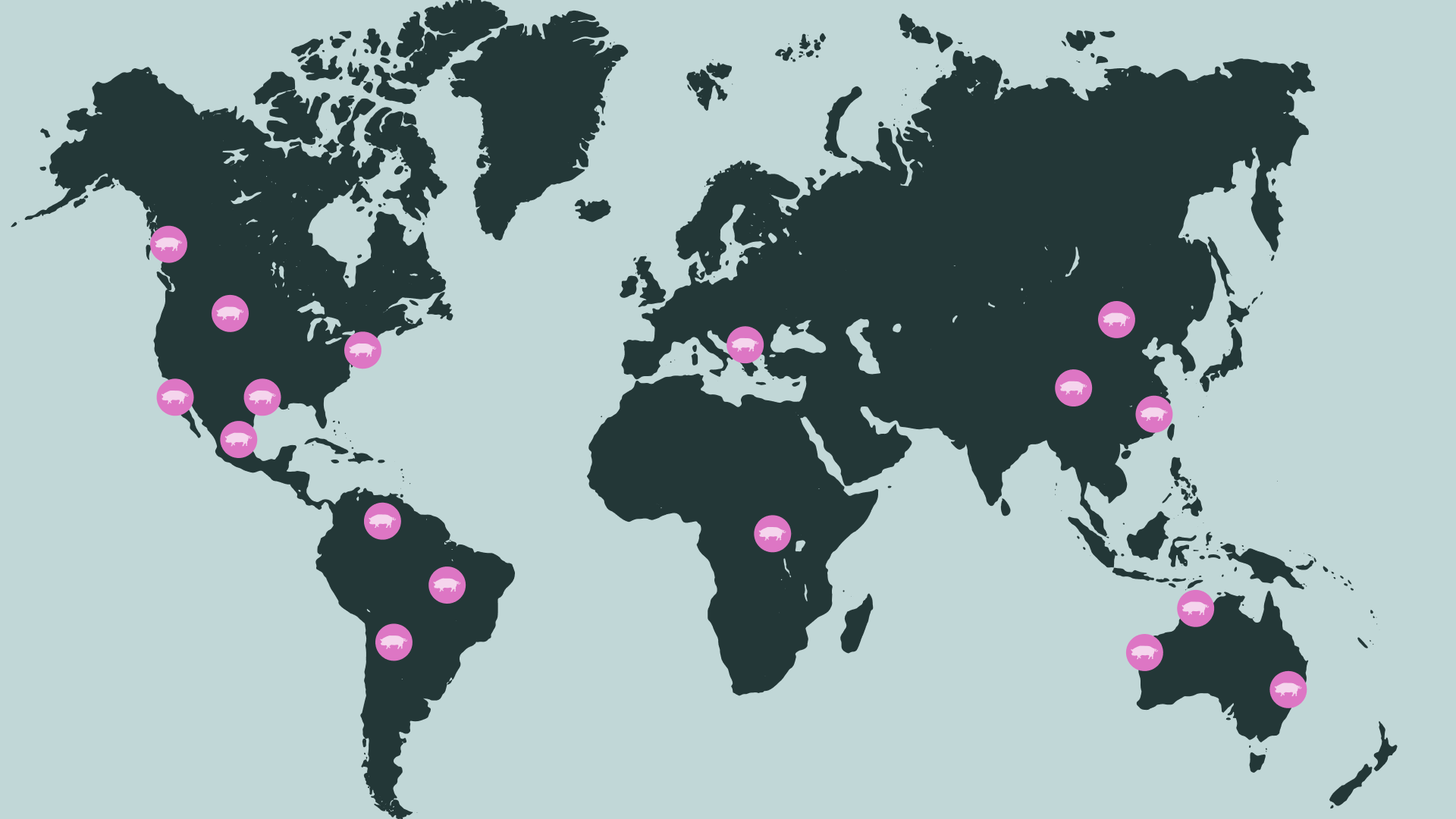

As human societies developed and expanded, so did domesticated pigs. The spread of agriculture and human migration facilitated the movement of pigs across vast distances. From the Near East, pigs spread into Europe and North Africa, while those from East Asia spread throughout the continent and eventually into Southeast Asia.

In Europe, pigs became integral to early farming communities, valued for their ability to convert various food sources into meat. By the time of the Roman Empire, pigs were widespread across Europe, and their meat was a staple of the Roman diet. In East Asia, particularly China, pigs held cultural significance, symbolizing wealth and prosperity. The expansion of Chinese agriculture and the spread of Buddhism further promoted the spread of pigs throughout Asia. (In some Buddhist communities, particularly in East Asia, pork became a permissible food for those who did not strictly follow vegetarianism. This created a demand for pork, contributing to the spread of pig farming.)

The spread of pigs to Africa and the Americas occurred much later, primarily due to European exploration and colonization. In Africa, pigs were introduced by European settlers and traders. In the Americas, pigs arrived with Spanish explorers in the 16th century. Hernán Cortés brought pigs to Mexico in 1519, where they quickly adapted and became a staple in the diets of both colonists and indigenous peoples.

Chapter 3 – From Pig to Pork

The word “pork” exemplifies the historical dynamics between the Anglo-Saxons and Normans following the Norman Conquest of 1066. Before the conquest, the inhabitants of England spoke Old English, a Germanic language. The word for pig in Old English was “swīn,” related to the modern word “swine.” After the Normans invaded, they introduced Old Norman (a Romance language) and established themselves as the ruling class.

The Anglo-Saxon peasants who raised animals continued using their native words, like “pig” and “swine,” while the Normans, who consumed the meat, used their own terminology. The Old Norman word “porc” (from Latin “porcus”) became the term for the meat once prepared for eating. Over time, this dual vocabulary became entrenched in English: Pig (animal) → Pork (meat). Cow (animal) → Beef (meat, from Old French “boeuf”). Sheep (animal) → Mutton (meat, from Old French “mouton”). Calf (animal) → Veal (meat, from Old French “veau”).

This pattern reflects the socio-linguistic blending that occurred after the Norman Conquest and is unique to English.

Chapter 4 – Feral Goes Viral

South America

In the 16th century, after Cortés brought pigs to Mexico, they were kept in settlements but also allowed to roam freely, leading some pigs to become feral. In Australia, pigs were introduced with the First Fleet in 1788 and soon became one of the most widespread species. Feral pigs in Australia, known locally as “wild boar” or “feral pigs,” became significant invasive species, causing extensive damage to crops, vegetation, and ecosystems.

Australia

Pigs were introduced to Australia with the arrival of the First Fleet in 1788. The First Fleet was the group of ships that established the first European colony in Australia, at Port Jackson (now Sydney). The fleet carried livestock, including pigs, to provide a stable food source for the settlers. Pigs were taken everywhere where the settlers invaded – and soon became the most wide-spread species. And, as were sometimes allowed to roam freely, feral pig populations occured. Feral pigs in Australia, known locally as “wild boar” or simply “feral pigs” became one of the most significant invasive species in Australia, causing extensive damage to crops, native vegetation, and ecosystems. Feral pigs also pose a threat to native wildlife and contribute to the spread of diseases.

North America

In the U.S., pigs were first brought by Columbus in 1493 and later by Hernando de Soto in 1539. As De Soto’s expedition moved through the southeastern United States, pigs either escaped or were left behind, leading to the establishment of feral pig populations. These feral pigs, sometimes called “razorbacks,” spread quickly across the region.

Chapter 5 – Pigs in the War – a little American Pig History

As colonies developed, pigs were primarily imported from England and Spain. With the growth of larger farms in the Midwest, where corn was both abundant and inexpensive, pig populations expanded rapidly. By the mid-1800s, the states with the highest corn production also became the leading centers for pig farming.

In America, pig breeds were traditionally categorized into two types: lard and bacon. Lard breeds were compact, thick-bodied pigs with short legs, known for fattening quickly on corn and producing meat with a high fat content. In contrast, bacon pigs were long, lean, and muscular, typically fed high-protein, low-energy diets, including legumes, small grains, turnips, and dairy byproducts. These pigs grew more slowly, developing more muscle than fat. The majority of American pig breeds fell into the lard category, with only the Yorkshire and Tamworth breeds classified as bacon types.

During World War II, the demand for lard surged as it became essential for manufacturing explosives. With most lard diverted for military use, people turned to vegetable oils for cooking, and lard never regained its former popularity after the war. At the same time, petrochemicals and synthetic nitroglycerine replaced lard in industrial and military applications. This led to a collapse in the lard market, prompting a significant shift in pig breeding practices. Breeders began to focus on producing leaner meat by selecting pigs for muscling rather than fattening, especially when fed corn.

The most popular breeds, such as Berkshire, Duroc, Hampshire, Poland China, and Yorkshire, adapted well to this change, benefiting from their genetic diversity. However, many of the less popular lard breeds were neglected and eventually disappeared. Today, only three traditional lard-type breeds remain: the Choctaw, Guinea Hog, and Mulefoot.

Chapter 6 – From Extensive to Intensive

Traditional Pig Husbandry: Extensive Systems.

Historically, pigs were raised in “extensive” systems, where they roamed freely and foraged for food. They were often fed food waste and agricultural by-products, making this approach economical and sustainable. Pigs were sometimes turned out into fields after harvest to glean remaining crops, providing additional food and helping clear fields.

Modern Pig Husbandry: Intensive Systems.

Today, most pigs in industrialized societies are raised in “intensive” systems. Pigs are kept in large, climate-controlled buildings, known as Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), designed to maximize efficiency and control over the environment. Modern pigs are fed a carefully formulated diet of high-energy grains, such as corn and soybeans, to optimize growth, meat quality, and feed efficiency. The shift to intensive farming has led to a decline in the diversity of pig breeds, with many traditional breeds becoming rare or endangered.

Chapter 7 – From Evolution to Revolution

The evolution of pig husbandry has brought various side effects that must be addressed in modern society. Intensive systems have increased pork production efficiency, making pork more affordable and widely available. However, these systems have raised concerns about environmental sustainability and animal welfare.

The New Chapter – The Revolution with AI

AGRI-FOOD.AI’s PigBrother technology has revolutionized pig husbandry in three key areas:

Monitoring and Data Collection: PigBrother technology allows real-time monitoring of pigs using sensors and cameras that collect data on weight, movement, temperature, and feeding behavior. This data is analyzed to provide insights into the pigs’ health and well-being.

Predictive Analytics and Decision-Making: Advanced algorithms in PigBrother technology predict potential issues before they become problems, allowing for timely interventions. The system optimizes feeding schedules based on growth patterns, helping each pig reach its full potential. Machine vision and AI are used to measure livestock and follow fattening daily without needing to scale individuals.

Animal Welfare: PigBrother improves animal welfare by using AI and machine vision to detect anomalies without disturbing the animals. The technology enhances farm efficiency, reducing human labor and increasing profitability

Open the gates to the future with AGRI-FOOD.AI ! Discover customized solutions with our experts! With us, the future is: now.

2024-08-16

2024-08-16  PODCAST

PODCAST

share

share

Our website uses cookies

Our website uses cookies